For more interesting stories on Navasota and surrounding counties visit :

www.russellcushman.blogspot.com

www.russellcushman.blogspot.com

NEVER FORGET!! Navasota's Morris Hoffman was one of the first American Allied soldiers to step through the Dachau Concentration Camp gate in 1945, freeing what remained of its prisoners. After the war, Morris married a local girl, Sarah Silverstein. In 1945 he was but 21 years old and later said “it was the blackest and most horrible day of my life.” Mr. Hoffman, we will not forget!

Kathy Day, retired Navasota High School history teacher, helped to bring Hoffman’s story again to our attention. (Please note the added information provided by Virginia French.)

Kathy says: Mr. Hoffman spoke to my class circa 1994-95. He had not talked about his experience of liberating Dachau until some guy in California (where Hoffman was on vacation) stated that the Holocaust was a lie. Then he decided he needed to tell his story.. He first spoke to a history class at TAMU, then came to speak to my history classes. He read what I have copied off. His store was Silverstein's- located where the Navasota Emporium is now. HIs wife was a Silverstein- which is the connection. After the filming of Schindler's List- there was an effort by Spielberg and others to get all the people that were witness to the Holocaust on film before they died. A group came out and interviewed Hoffman and filmed it. I think the film is with the USC Shoah Foundation- which it can be viewed at TAMU. I've never been up to see it- hope to do it sometime.

Kathy Day, retired Navasota High School history teacher, helped to bring Hoffman’s story again to our attention. (Please note the added information provided by Virginia French.)

Kathy says: Mr. Hoffman spoke to my class circa 1994-95. He had not talked about his experience of liberating Dachau until some guy in California (where Hoffman was on vacation) stated that the Holocaust was a lie. Then he decided he needed to tell his story.. He first spoke to a history class at TAMU, then came to speak to my history classes. He read what I have copied off. His store was Silverstein's- located where the Navasota Emporium is now. HIs wife was a Silverstein- which is the connection. After the filming of Schindler's List- there was an effort by Spielberg and others to get all the people that were witness to the Holocaust on film before they died. A group came out and interviewed Hoffman and filmed it. I think the film is with the USC Shoah Foundation- which it can be viewed at TAMU. I've never been up to see it- hope to do it sometime.

This is Mr. Morris Hoffman's story:

My name is Morris Hoffman. I live in Navasota, Texas with my wife Sarah Silverstein Hoffman. I have been in the grocery business and a Pecan Broker for the last 40 years. We have two children: Rochelle Hoffman Gedaly and her husband Jerry of Andover, Mass.; and Myron Hoffman and his wife Elaine of Houston, Texas. We also have 4 grandchildren. I was part of the American forces that liberated Dachau Concentration Camp on April 30, 1945. It was the blackest and most horrible day of my life. I was 21 years old and lived in Marshalltown, Iowa when I entered the army in World War II.

In 1944, I was shipped overseas on the Queen Elizabeth, landing at La Harve, France. I joined up with the 157th Infantry, 7th Army, 45th Division called the “Thunderbirds.” At that time my rank was a Staff Sgt. During the European Campaign, I received the Bronze Star for Meritorious service in the European Theater of WWII. The men in my unit knew that I was an Orthodox Jew, and traded C-rations with me so that I could keep our dietary laws.

We fought a three day battle through the Ziegfried Line called “The Tiger Teeth.” We also fought the Battle of the Rhine River and drove the Germans across France back into Germany and we ended up in Munich. A week before this came about, we were told we were going to liberate a prisoner of war camp. Little did we know what was in store for us. We thought we were going to liberate some of our own prisoners.

It was April 29, 1945 at 10:00 in the morning when our company moved out to take a small town northwest of Munich. My army unit surrounded the camp located inside the Dachau city limits. As we approached the concentration camp, we saw the towers, electric barbed wire fences, and moat that surrounded the camp. Other members of our unit knew that I was of the Jewish faith and came back to tell me to be prepared to see all the terrible things the Nazis had done to our people.

As Sgt. I was leading a squad of soldiers when we entered the gates of Dachau. When we reached the parade grounds, the stench made us sick. We saw the barracks with naked dead bodies stacked like cord-wood. They looked like sacks of bones. As we entered other parts of the camp we saw a railroad spur with 8 box card half full of naked bodies being shipped out by the Nazis, but we did not know where. The prisoners that were still living in the barracks were half dead from torture, disease and starvation-emaciated faces and bodies. The prisoners had their heads shaved and wore black and white striped uniforms. Jewish prisoners wore patches – a yellow Star of David—with letters in Germany saying Jude (Jew) on their clothes. There were other prisoners of many faiths and countries. Some of the prisoners were so weak that they could not stand up. Some had work duty, but were given very little food. There was a pit filled with naked dead bodies, but the Nazis were unable to cover them because our American soldiers advanced so fast. They also buried bodies next to the railroad tracks hoping no one would see them. We found corpses not completely consumed by flames in the furnaces of the camp crematoriums. There were also baskets of gold eye glasses and gold fillings that the Nazis left behind. In the barracks, there were prisoners still alive that were stacked in bunks 4 high. All had numbers tattoed on their arms with blue dye so that the Germans could keep records.

Two Jewish students who were prisoners asked to speak to a Jewish soldier, so they brought them to me, being the only one they could find. They were Americans studying at the University of Munich and were captured and brought to Dachau. They wanted to join our unit, but our Captain said that they could not as they were not trained as soldiers and need medical attention. Documentation also had to be sent back to the US.

All prisoners at the camp were told that we could not let them go until the medical team got to the camp to examine them. The Army set up field kitchen to serve them something to eat and drink, but some were so weak that nothing could save them.

It was very difficult to keep the American soldiers from shooting the Nazis that were captured after seeing the horrors that had taken place in the camp. The American officers brought the Mayor of Dachau and its citizens to view all of the atrocities that the Nazis had committed. They denied knowing that any of this had happened.

Since I was a lead of my squad, the Captain asked me to lead an honor guard across the parade ground. I was given the honor of carrying the American flag. Three other soldiers carried rifles and the Battalion flag. The sound of the prisoners hollering rings in my ears, even though it has been almost 49 years ago. They were so excited that I was afraid we might be hurt if they got over the fence.

The memories I have of Dachau are still impossible for me to comprehend or forget. It was many years before I was able to talk about them. I am still unable to believe that one human being could do such horrible things to another. I hope and pray these atrocities will never be seen again.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Virginia French remembers: “Sarah (Silverstein) Hoffman was the daughter of Ben and Fannie (Isenberg) Silverstein. They moved to

Navasota in 1916 and joined the Isenbergs in selling fruit...called Isenberg and Silverstein Produce. In 1936 Ben Silverstein bought out the produce business and opened a grocery store located where the Emporium is now in business. In 1962 Morris and Sarah Hoffman bought it and it was called Lucky Seven. The pecan warehouse was located behind the store...it was where most of Navasota bought their groceries...I know my family went every Saturday and I looked forward to going with my Mama shopping....They would sell Christmas trees out in front of the store every Christmas and that was always fun to go and pick out our tree. Morris and Sarah (Silverstein) Hoffman were among the last Jewish to live in Navasota.”

Mr. Hoffman died in 1999 and Sarah in December 2013. They are both buried in the Adath Israel Cemetery in Houston.

My name is Morris Hoffman. I live in Navasota, Texas with my wife Sarah Silverstein Hoffman. I have been in the grocery business and a Pecan Broker for the last 40 years. We have two children: Rochelle Hoffman Gedaly and her husband Jerry of Andover, Mass.; and Myron Hoffman and his wife Elaine of Houston, Texas. We also have 4 grandchildren. I was part of the American forces that liberated Dachau Concentration Camp on April 30, 1945. It was the blackest and most horrible day of my life. I was 21 years old and lived in Marshalltown, Iowa when I entered the army in World War II.

In 1944, I was shipped overseas on the Queen Elizabeth, landing at La Harve, France. I joined up with the 157th Infantry, 7th Army, 45th Division called the “Thunderbirds.” At that time my rank was a Staff Sgt. During the European Campaign, I received the Bronze Star for Meritorious service in the European Theater of WWII. The men in my unit knew that I was an Orthodox Jew, and traded C-rations with me so that I could keep our dietary laws.

We fought a three day battle through the Ziegfried Line called “The Tiger Teeth.” We also fought the Battle of the Rhine River and drove the Germans across France back into Germany and we ended up in Munich. A week before this came about, we were told we were going to liberate a prisoner of war camp. Little did we know what was in store for us. We thought we were going to liberate some of our own prisoners.

It was April 29, 1945 at 10:00 in the morning when our company moved out to take a small town northwest of Munich. My army unit surrounded the camp located inside the Dachau city limits. As we approached the concentration camp, we saw the towers, electric barbed wire fences, and moat that surrounded the camp. Other members of our unit knew that I was of the Jewish faith and came back to tell me to be prepared to see all the terrible things the Nazis had done to our people.

As Sgt. I was leading a squad of soldiers when we entered the gates of Dachau. When we reached the parade grounds, the stench made us sick. We saw the barracks with naked dead bodies stacked like cord-wood. They looked like sacks of bones. As we entered other parts of the camp we saw a railroad spur with 8 box card half full of naked bodies being shipped out by the Nazis, but we did not know where. The prisoners that were still living in the barracks were half dead from torture, disease and starvation-emaciated faces and bodies. The prisoners had their heads shaved and wore black and white striped uniforms. Jewish prisoners wore patches – a yellow Star of David—with letters in Germany saying Jude (Jew) on their clothes. There were other prisoners of many faiths and countries. Some of the prisoners were so weak that they could not stand up. Some had work duty, but were given very little food. There was a pit filled with naked dead bodies, but the Nazis were unable to cover them because our American soldiers advanced so fast. They also buried bodies next to the railroad tracks hoping no one would see them. We found corpses not completely consumed by flames in the furnaces of the camp crematoriums. There were also baskets of gold eye glasses and gold fillings that the Nazis left behind. In the barracks, there were prisoners still alive that were stacked in bunks 4 high. All had numbers tattoed on their arms with blue dye so that the Germans could keep records.

Two Jewish students who were prisoners asked to speak to a Jewish soldier, so they brought them to me, being the only one they could find. They were Americans studying at the University of Munich and were captured and brought to Dachau. They wanted to join our unit, but our Captain said that they could not as they were not trained as soldiers and need medical attention. Documentation also had to be sent back to the US.

All prisoners at the camp were told that we could not let them go until the medical team got to the camp to examine them. The Army set up field kitchen to serve them something to eat and drink, but some were so weak that nothing could save them.

It was very difficult to keep the American soldiers from shooting the Nazis that were captured after seeing the horrors that had taken place in the camp. The American officers brought the Mayor of Dachau and its citizens to view all of the atrocities that the Nazis had committed. They denied knowing that any of this had happened.

Since I was a lead of my squad, the Captain asked me to lead an honor guard across the parade ground. I was given the honor of carrying the American flag. Three other soldiers carried rifles and the Battalion flag. The sound of the prisoners hollering rings in my ears, even though it has been almost 49 years ago. They were so excited that I was afraid we might be hurt if they got over the fence.

The memories I have of Dachau are still impossible for me to comprehend or forget. It was many years before I was able to talk about them. I am still unable to believe that one human being could do such horrible things to another. I hope and pray these atrocities will never be seen again.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Virginia French remembers: “Sarah (Silverstein) Hoffman was the daughter of Ben and Fannie (Isenberg) Silverstein. They moved to

Navasota in 1916 and joined the Isenbergs in selling fruit...called Isenberg and Silverstein Produce. In 1936 Ben Silverstein bought out the produce business and opened a grocery store located where the Emporium is now in business. In 1962 Morris and Sarah Hoffman bought it and it was called Lucky Seven. The pecan warehouse was located behind the store...it was where most of Navasota bought their groceries...I know my family went every Saturday and I looked forward to going with my Mama shopping....They would sell Christmas trees out in front of the store every Christmas and that was always fun to go and pick out our tree. Morris and Sarah (Silverstein) Hoffman were among the last Jewish to live in Navasota.”

Mr. Hoffman died in 1999 and Sarah in December 2013. They are both buried in the Adath Israel Cemetery in Houston.

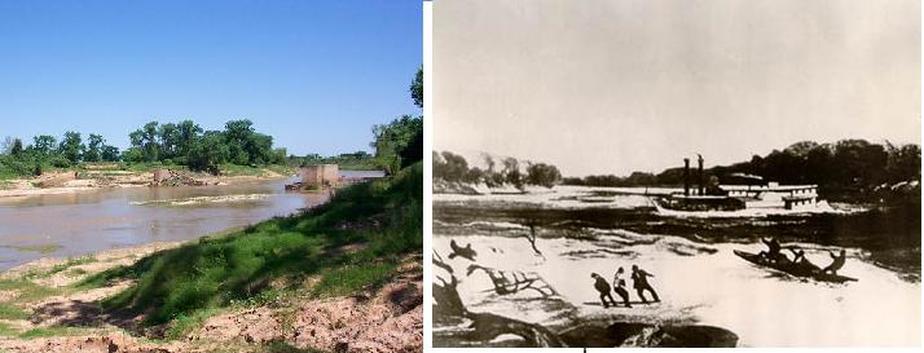

LOCKS ON THE BRAZOS

Betty Dunn

Steamboats on the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers are not hard to envision but on the Brazos River??? Yes – they were there with captains valiantly trying to force their way from the Gulf of Mexico past the once bustling port of Washington on the Brazos, past Hidalgo Falls as far as Port Sullivan just shy of Waco.

Beginning in the 1820s steamboats carried tons and tons of supplies up the Brazos River to docks at Washington on the Brazos and beyond, and tons and tons of cotton bales back down river to market. The town where the Republic of Texas constitution was signed in March 1836, became the business and social center of the Brazos east and west bank region. When the steamboats approached the Washington docks with bells and whistles sounding, the entire town rushed to the water’s edge. Balls and parties flourished along with the barter and trade. The railroad eventually displaced the steamboats and shuttered the Washington on the Brazos community. The U. S. Government’s Army Corps of Engineers worked diligently in the early 1900s in an effort to keep the Brazos River navigable by building several locks up river from Washington. Remnants of these locks exist today.

The American Canal Society Guide, in a report dated in 1981, states that the Brazos River navigation effort by the Corps of Engineers began in 1905 with the object of making the river navigable as far as Waco, 450 miles from the Gulf of Mexico. Eight concrete locks and dams were planned, all between Hidalgo Falls, north of Washington-on-the-Brazos and Waco, a distance of 176 miles. Severe flooding in 1913 and 1921, as well as the suspension of work during World War I, led to the final abandonment in 1922 with only 3 locks under construction. When the Society issued the 1981 report, the locks were still in good condition but without the gates and without some of the metalwork salvaged during WWII. Just below Waco, Lock 8 in the early 1980s was in the middle of a field because of a shift in the river during the 1921 flood. The report suggested that a sternwheeler be put in the river at Washington-on-the-Brazos as a relic of steamboat days for excursions up river 4 miles to Lock 1 just below the Rocks where, in 2001, a 13-acre private Texas Rivers Protection Association park was established.

Kayakers and canoeists now glide by Lock 1’s concrete remnants that this columnist recently visited and photographed near Navasota. For more historical information on the Brazos’s steamboat era, read the book, Sandbars and Sternwheelers, Navigation of the Brazos, written by Pamela A. Puryear and Nath Winfield, Jr., published by the Texas A & M University Press.

DANCE BROTHERS CIVIL WAR PISTOLS

Copied with permission of Betty Dunn

A few miles north of Anderson on FM 244 off Highway 90 is Texas Historical Marker #8603. It states: “Site of a munition factory of the Southern Confederacy, established 1861, in operation until 1865.” It was here that the J. H. Dance & Brothers Company, maker of firearms, established a Colt-type pistol factory.

They had relocated from Brazoria County in the face of a Union attack on the Gulf Coast. If anyone happens to own one of their less than 500 manufactured pistols they not only have a valuable, sought after and desirable firearm but an historic piece of Texas history. It is estimated that they manufactured about 350 of the .44 caliber revolvers and about 135 of the .36 caliber. The factory also produced cannon balls, bayonets, sabers, swords and gun powder.

The Dance brothers first arrived in Brazoria County about 1848 from North Carolina via Alabama. By 1858 they had built a large home at the Brazos River port of East Columbia and established a metal and woodworking factory named J. H. Dance and Company. The brothers were James Henry, David Etheridge, George, and Isaac. Early on the company also manufactured gristmills and cotton gins.

At the beginning of the Civil War, though the brothers enlisted with the 35th Texas Cavalry, they were detailed back to their factory because of their metal working skills. As the Union Army occupied Matagorda Island just off Texas, threatening invasion of the Gulf Coast, the Dance brothers moved to the Anderson area to manufacture firearms for the Confederacy. It was during this time that brother Isaac died of measles.

It is believed that Otto and Alexander Erichson, sons of famed German immigrant gunsmith Gustav Erichson of Houston, worked at the Dance munitions factory at Anderson. At least one of the Dance revolvers survives stamped “G. Erichson. Houston. Texas.”

When the war ended the Dance brothers closed the Anderson facility and returned to East Columbia to restore their factory while adding the manufacture of furniture. The 1900 hurricane ruined the factory. It was never rebuilt.

Copied with permission of Betty Dunn

A few miles north of Anderson on FM 244 off Highway 90 is Texas Historical Marker #8603. It states: “Site of a munition factory of the Southern Confederacy, established 1861, in operation until 1865.” It was here that the J. H. Dance & Brothers Company, maker of firearms, established a Colt-type pistol factory.

They had relocated from Brazoria County in the face of a Union attack on the Gulf Coast. If anyone happens to own one of their less than 500 manufactured pistols they not only have a valuable, sought after and desirable firearm but an historic piece of Texas history. It is estimated that they manufactured about 350 of the .44 caliber revolvers and about 135 of the .36 caliber. The factory also produced cannon balls, bayonets, sabers, swords and gun powder.

The Dance brothers first arrived in Brazoria County about 1848 from North Carolina via Alabama. By 1858 they had built a large home at the Brazos River port of East Columbia and established a metal and woodworking factory named J. H. Dance and Company. The brothers were James Henry, David Etheridge, George, and Isaac. Early on the company also manufactured gristmills and cotton gins.

At the beginning of the Civil War, though the brothers enlisted with the 35th Texas Cavalry, they were detailed back to their factory because of their metal working skills. As the Union Army occupied Matagorda Island just off Texas, threatening invasion of the Gulf Coast, the Dance brothers moved to the Anderson area to manufacture firearms for the Confederacy. It was during this time that brother Isaac died of measles.

It is believed that Otto and Alexander Erichson, sons of famed German immigrant gunsmith Gustav Erichson of Houston, worked at the Dance munitions factory at Anderson. At least one of the Dance revolvers survives stamped “G. Erichson. Houston. Texas.”

When the war ended the Dance brothers closed the Anderson facility and returned to East Columbia to restore their factory while adding the manufacture of furniture. The 1900 hurricane ruined the factory. It was never rebuilt.

Lynn Grove Church

by Betty Dunn

The little church that could sits on a sharp curve of County Road 319, north about 1 ½ miles of State Highway 2, in the southwest corner of Grimes County. It thrives well over one hundred years since 1888. It is Lynn Grove Methodist Church in its namesake community. Just this summer of 2014 it received a Texas Historical Commission historical marker. Today, its well maintained church yard welcomes each Sunday morning up to and sometimes over just 20 mere parishioners.

The community of Lynn Grove is mainly the geographic area east of Highway 6 to FM 362, through the old Retreat area and from Grassy Creek to the Waller County line. It was named for the vast forest of Linden trees. Much of the area lies in the early Jared E. Groce survey.

The church itself was organized in 1888 and its first permanent building was erected about 1892. History tells us the site was deeded by J. H. Muldrew to C. G. Vickers, J. L. Shine and Z. (Zach) S. Weaver, church trustees. Descendants still live in the area and attend the church services.

Z. (Zach) S. Weaver, a carpenter who became a renowned beekeeper, built the 18 inch wide church pews of pine boards. Today, they still seat the worshipers.

by Betty Dunn

The little church that could sits on a sharp curve of County Road 319, north about 1 ½ miles of State Highway 2, in the southwest corner of Grimes County. It thrives well over one hundred years since 1888. It is Lynn Grove Methodist Church in its namesake community. Just this summer of 2014 it received a Texas Historical Commission historical marker. Today, its well maintained church yard welcomes each Sunday morning up to and sometimes over just 20 mere parishioners.

The community of Lynn Grove is mainly the geographic area east of Highway 6 to FM 362, through the old Retreat area and from Grassy Creek to the Waller County line. It was named for the vast forest of Linden trees. Much of the area lies in the early Jared E. Groce survey.

The church itself was organized in 1888 and its first permanent building was erected about 1892. History tells us the site was deeded by J. H. Muldrew to C. G. Vickers, J. L. Shine and Z. (Zach) S. Weaver, church trustees. Descendants still live in the area and attend the church services.

Z. (Zach) S. Weaver, a carpenter who became a renowned beekeeper, built the 18 inch wide church pews of pine boards. Today, they still seat the worshipers.

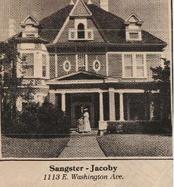

Sangster/Jacoby Home

The Sangster home was built in 1901 with a Queen Ann revival style in the exterior. R. A. "Buck" Sangster had the home built and his brother, W.W. Sangster bought the home in 1929. It remained in the family until 1965 when Charles & Emma Jacoby bought it.

The home has 12 rooms, decorated with curly red pine, a type of wood that is now extinct. Sliding doors between the double parlors shows the distinctive swirl in the wood.

All the old homes in this era had double parlors. One parlor would be used for a music room for the ladies or a library where men could meet and talk and smoke cigars.

The rooms have high ceilings, which give an open spacious feeling. The front parlor is framed with a lacy lattice design, the front doors are beveled lead glass and there are several windows that are stained glass.

The downstairs porch wraps around the front of the house, and the upstairs back porch gives a great view of the back area. The house has 6 fireplaces, 3 are upstairs and 3 are downstairs. The house was painted originally white, but the Jacoby's painted the home a unique mixture of a mauve gray color when he bought it.

The Sangster home was built in 1901 with a Queen Ann revival style in the exterior. R. A. "Buck" Sangster had the home built and his brother, W.W. Sangster bought the home in 1929. It remained in the family until 1965 when Charles & Emma Jacoby bought it.

The home has 12 rooms, decorated with curly red pine, a type of wood that is now extinct. Sliding doors between the double parlors shows the distinctive swirl in the wood.

All the old homes in this era had double parlors. One parlor would be used for a music room for the ladies or a library where men could meet and talk and smoke cigars.

The rooms have high ceilings, which give an open spacious feeling. The front parlor is framed with a lacy lattice design, the front doors are beveled lead glass and there are several windows that are stained glass.

The downstairs porch wraps around the front of the house, and the upstairs back porch gives a great view of the back area. The house has 6 fireplaces, 3 are upstairs and 3 are downstairs. The house was painted originally white, but the Jacoby's painted the home a unique mixture of a mauve gray color when he bought it.

Oakland Cemetery

In Navasota’s Oakland Cemetery are the mortal remains of three Methodist clergymen who were figures in the history of this Trans Brazos region. They are namely Rev. Martin Ruter, Rev. James Wesson and Rev. C. L. Spencer. The three impacted early Texas from 1837 to 1908.

For the "rest of the story' go to www.texascenterforregionalstudies.net and click under tab 'cemetery'.

In Navasota’s Oakland Cemetery are the mortal remains of three Methodist clergymen who were figures in the history of this Trans Brazos region. They are namely Rev. Martin Ruter, Rev. James Wesson and Rev. C. L. Spencer. The three impacted early Texas from 1837 to 1908.

For the "rest of the story' go to www.texascenterforregionalstudies.net and click under tab 'cemetery'.

The Lawrence Cemetery

copied with permission of Betty Dunn

Early 1830’s Grimes county pioneer settler Jared Groce knew a good man when he saw one. One of these men was Martin Byrd Lawrence. Groce gave Lawrence the equivalent of 100 acres just over the hill to the east of his Retreat land grant in southwest Grimes County as evidenced by a deed recorded in Volume M, page 385, Grimes County.

Lawrence had a valuable trade. He was a tanner and established the first tannery in Texas in 1833 that included a saddlers shop and shoe shop adjacent to Groce’s Retreat. Water was a necessity and the flowing waters of nearby Beason Creek fit the need. He also operated a saw mill.

Lawrence was the only son of George Lawrence and his wife. George and his brother Asa fought in the Revolutionary War to be captured by the British, taken to England and held prisoners of war until the Colonies won independence. The brothers stayed in England and were sea captains, but after Asa was lost at sea, George gave up maritime life, returned to America and married Elizabeth Byrd of Virginia. They lived near Knoxville, Tennessee and then relocated to Cape Girardeau, Missouri.

Lawrence, born on November 23, 1794, grew up and married Mariah Hart Davis, a first cousin of Jefferson Davis, who later became President of the Confederate States of America. To this union were born 12 children. Lawrence and his wife lived at Cape Girardeau following their marriage and later in Hempstead County, Arkansas where he first established a tannery.

In 1832, the lure of new land brought Lawrence and his family to Texas. They first settled in Austin’s Colony on the San Bernard River. Fearing the Indians and Mexican Army, they shortly moved north to Groce’s Retreat where it seemed safer. But incidents still did occur and Lawrence and his son, George, were in the party who tried to rescue Cynthia Ann Parker from the Indians. Martin and his son George also joined General Sam Houston’s Independence Army in January 1836. Houston became a personal friend and frequent visitor in the Lawrence home.

Lawrence died in November 1851 at the age of 57 years leaving his widow Mariah and children. He is buried on the hill above where the homestead had been built in what today is a small ‘hidden’ cemetery in a small grove of vine entwined trees surrounded by pasture a good mile off any roadway. There are only five known burials in what is locally known as the Lawrence Cemetery. Also buried there include Lawrence’s wife, Mariah, who died in August 1867 at the age of 63 years; a son Algernon Robert Lawrence, born June 1846, who died in June 1869 at the age of 23 of wounds received in the Civil War. Algernon’s burial is the last known in this cemetery.

Two small girls were the first to be buried in this cemetery. Sarah Elizabeth Lane, daughter of Harvey and Elizabeth (Shaw) Lane, born April 1837, who died at the age of 2 years in July 1839. Sallie Betsey Bennett, daughter of Charles A. and Pauline N. (Lawrence) Bennett, died November 28, 1868 at the age of 4 years, 9 months, 15 days. (The Bennetts lived at Courtney.) This grave of the grandchild of the Lawrence's, is surrounded by an iron picket fence and covered by a slab inscribed with doves and flowers. A lamb is at the head of the gravestone with an urn engraved “Sallie” as well as a poignant poetic verse: “ Sallie is dead, a child as sweet and fair as an opening rosebud in the morning air. Bound her pure urn let darknest cypress wave, Youth could not save her from an early grave. She was lovely, she was fair, and for awhile was given; An angel came, and claimed his own, and bore her home to heaven.”

Lawrence and his wife Mariah had five sons who served in the Civil War. The second son, Groce, was killed in the Battle of the Wilderness. The others were the eldest son, George, and then Edward, Ludwell and Algernon. George married Sallie Howell and reared a large family near Groce’s Retreat. Edward and Ludwell never married and were known around the region as Uncle Ned and Uncle Lud. As mentioned earlier Algernon died at the age of 23 of wounds suffered in the Civil War.

copied with permission of Betty Dunn

Early 1830’s Grimes county pioneer settler Jared Groce knew a good man when he saw one. One of these men was Martin Byrd Lawrence. Groce gave Lawrence the equivalent of 100 acres just over the hill to the east of his Retreat land grant in southwest Grimes County as evidenced by a deed recorded in Volume M, page 385, Grimes County.

Lawrence had a valuable trade. He was a tanner and established the first tannery in Texas in 1833 that included a saddlers shop and shoe shop adjacent to Groce’s Retreat. Water was a necessity and the flowing waters of nearby Beason Creek fit the need. He also operated a saw mill.

Lawrence was the only son of George Lawrence and his wife. George and his brother Asa fought in the Revolutionary War to be captured by the British, taken to England and held prisoners of war until the Colonies won independence. The brothers stayed in England and were sea captains, but after Asa was lost at sea, George gave up maritime life, returned to America and married Elizabeth Byrd of Virginia. They lived near Knoxville, Tennessee and then relocated to Cape Girardeau, Missouri.

Lawrence, born on November 23, 1794, grew up and married Mariah Hart Davis, a first cousin of Jefferson Davis, who later became President of the Confederate States of America. To this union were born 12 children. Lawrence and his wife lived at Cape Girardeau following their marriage and later in Hempstead County, Arkansas where he first established a tannery.

In 1832, the lure of new land brought Lawrence and his family to Texas. They first settled in Austin’s Colony on the San Bernard River. Fearing the Indians and Mexican Army, they shortly moved north to Groce’s Retreat where it seemed safer. But incidents still did occur and Lawrence and his son, George, were in the party who tried to rescue Cynthia Ann Parker from the Indians. Martin and his son George also joined General Sam Houston’s Independence Army in January 1836. Houston became a personal friend and frequent visitor in the Lawrence home.

Lawrence died in November 1851 at the age of 57 years leaving his widow Mariah and children. He is buried on the hill above where the homestead had been built in what today is a small ‘hidden’ cemetery in a small grove of vine entwined trees surrounded by pasture a good mile off any roadway. There are only five known burials in what is locally known as the Lawrence Cemetery. Also buried there include Lawrence’s wife, Mariah, who died in August 1867 at the age of 63 years; a son Algernon Robert Lawrence, born June 1846, who died in June 1869 at the age of 23 of wounds received in the Civil War. Algernon’s burial is the last known in this cemetery.

Two small girls were the first to be buried in this cemetery. Sarah Elizabeth Lane, daughter of Harvey and Elizabeth (Shaw) Lane, born April 1837, who died at the age of 2 years in July 1839. Sallie Betsey Bennett, daughter of Charles A. and Pauline N. (Lawrence) Bennett, died November 28, 1868 at the age of 4 years, 9 months, 15 days. (The Bennetts lived at Courtney.) This grave of the grandchild of the Lawrence's, is surrounded by an iron picket fence and covered by a slab inscribed with doves and flowers. A lamb is at the head of the gravestone with an urn engraved “Sallie” as well as a poignant poetic verse: “ Sallie is dead, a child as sweet and fair as an opening rosebud in the morning air. Bound her pure urn let darknest cypress wave, Youth could not save her from an early grave. She was lovely, she was fair, and for awhile was given; An angel came, and claimed his own, and bore her home to heaven.”

Lawrence and his wife Mariah had five sons who served in the Civil War. The second son, Groce, was killed in the Battle of the Wilderness. The others were the eldest son, George, and then Edward, Ludwell and Algernon. George married Sallie Howell and reared a large family near Groce’s Retreat. Edward and Ludwell never married and were known around the region as Uncle Ned and Uncle Lud. As mentioned earlier Algernon died at the age of 23 of wounds suffered in the Civil War.

THE TWO REMARKABLE WESSONS

By Betty Dunn

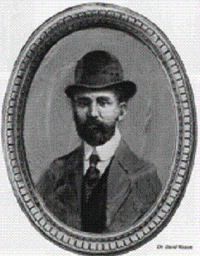

Henry S. Wesson and David Wesson (left photo, 1861-1934), though they may or may not have been distant kin, their distinctly different yet remarkable paths may well have crossed over a popular kitchen cooking product – Wesson Oil. The once worthless by-product of the cottonseed seemingly united their names at the Schumacher Cotton Oil Mill in Navasota.

Henry, a grandson of the Navasota mill’s founder Henry Schumacher, served as president of the Navasota mill in the early 1950s. By then, David, the chemist credited with developing the cooking oil that revolutionized a waste product into a burgeoning kitchen industry, had died in New York in 5/22/1934. It was 1899, when David, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology chemistry graduate and faculty member then researching with the Southern Cotton Oil Company, developed the process of converting cottonseed oil into a cooking product. Though the process was never patented it, today, still carries his name – Wesson Oil.

David and Henry Wesson probably never met over their lifetimes that spanned nearly two generations. Whether they were very distant cousins must be left to diligent genealogists. Limited research reveals that David’s direct ancestors came from England to Salem, Massachusetts in the 1640s, while Henry’s ancestors came to Virginia from England over two centuries later in the mid-1850s.

Henry’s paternal grandfather was Rev. J. M. Wesson, a 1860s Methodist minister of the Grimes County and Trans-Brazos region, who, according to the 1880 U. S. Census records, was born in England in 1832. Rev. Wesson is often mentioned in local church history including that of Plantersville, Tx. as the co- founder of a ministry among local freedmen shortly following the Civil War.

Rev. Wesson married Nancy Byrd in Navasota in the early 1860s. Nancy was the daughter of Macajah and Hannah (Bradbury) Byrd, of Old Washington, early 1820s Austin Colony settlers. (Her father died in 1830 shortly before Nancy’s birth.) The Reverend and Nancy’s son, Walter Blake Wesson, was born January 27, 1866. Walter married Henry Schumacher’s daughter, Ada. Their son, Henry, who was to eventually become president of his grandfather’s business, was born November 23, 1896. Henry, obviously named for his maternal grandfather, grew up in the shadow and workings of the Schumacher Cotton Mill in Navasota. Though Henry’s father Walter was a bookkeeper at the Schumacher mill in the 1920 U. S. Census record and then a vice-president in the 1930 census data, his son, Henry, took a much different path. Henry followed in the path of his mother Ada, who was a nationally known musician. Henry became a world known musician.

In 1920 Henry was living in New York City where he was organist for three years at the Episcopal Church of the Holy Apostles. The census records show him as a boarder at a house in Manhattan. Only a street or two away was another Manhattan boarder studying music from Pueblo, Colorado – Ida M. Koen. In the 1930 census records, Henry and Ida are married and the parents of two daughters, Emma S., age 8, born in New York and Ida K.,born in South Carolina. At this time the family was living in Nashville, Tennessee where Henry was a music teacher and student at the renowned Ward-Belmont School of Music. He was also the distinguished 1st carillonneur of the school’s 1928 installed carillon of 23 bells. Henry, over time, also composed music for carillons. Both he and Ida had studied from the very best teachers.

The 1940 U. S. Census has Henry and family returned to Navasota. They are residing in the home with Henry’s father, Walter. Henry is recorded as a pipe organ teacher with his wife, Ida, listed as a piano teacher in their private music studio. They taught music to hundreds of Navasota area students. Their daughter Ida dated a Texas A & M corps cadet, Colbert Coldwell of near El Paso. Following Coldwell’s World War II service they were married in March 1945. Meantime Henry’s father Walter, by now head of the Schumacher Cotton Oil Mill, had died in November 1944. Henry’s mother, Ada Schumacher, died the following February. It was then that Henry’s son-in-law Coldwell became the cotton mill manager until 1950, when he resigned and the Coldwell family moved to Clint, Texas to manage his family’s farm. (Coldwell, living in El Paso, died in May 2010 and his wife Ida K. (Wesson), Henry’s daughter, died in June 2013.)

Henry, in 1950, stepped into full management of the Schumacher mill until it ceased operation in 1954. (The Schumacher Cotton Mill stood in Navasota where the Brookshire Grocery store is now located.) Henry died in June 1964 but was preceded in death by his wife, Ida (Koen), nearly ten years earlier in November 1955. All the Wesson burials are in the Oakland Cemetery in Navasota.

With the advent of the development of Wesson Oil from the by-product of cottonseed oil, it can only be a given that some of the cottonseed oil produced by the Schumacher mill became a staple of the popular cooking oil. Is it possible that Henry, at least while he was living in New York in the 1920s, ever met David Wesson, the chemist, who died there in 1934?

By Betty Dunn

Henry S. Wesson and David Wesson (left photo, 1861-1934), though they may or may not have been distant kin, their distinctly different yet remarkable paths may well have crossed over a popular kitchen cooking product – Wesson Oil. The once worthless by-product of the cottonseed seemingly united their names at the Schumacher Cotton Oil Mill in Navasota.

Henry, a grandson of the Navasota mill’s founder Henry Schumacher, served as president of the Navasota mill in the early 1950s. By then, David, the chemist credited with developing the cooking oil that revolutionized a waste product into a burgeoning kitchen industry, had died in New York in 5/22/1934. It was 1899, when David, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology chemistry graduate and faculty member then researching with the Southern Cotton Oil Company, developed the process of converting cottonseed oil into a cooking product. Though the process was never patented it, today, still carries his name – Wesson Oil.

David and Henry Wesson probably never met over their lifetimes that spanned nearly two generations. Whether they were very distant cousins must be left to diligent genealogists. Limited research reveals that David’s direct ancestors came from England to Salem, Massachusetts in the 1640s, while Henry’s ancestors came to Virginia from England over two centuries later in the mid-1850s.

Henry’s paternal grandfather was Rev. J. M. Wesson, a 1860s Methodist minister of the Grimes County and Trans-Brazos region, who, according to the 1880 U. S. Census records, was born in England in 1832. Rev. Wesson is often mentioned in local church history including that of Plantersville, Tx. as the co- founder of a ministry among local freedmen shortly following the Civil War.

Rev. Wesson married Nancy Byrd in Navasota in the early 1860s. Nancy was the daughter of Macajah and Hannah (Bradbury) Byrd, of Old Washington, early 1820s Austin Colony settlers. (Her father died in 1830 shortly before Nancy’s birth.) The Reverend and Nancy’s son, Walter Blake Wesson, was born January 27, 1866. Walter married Henry Schumacher’s daughter, Ada. Their son, Henry, who was to eventually become president of his grandfather’s business, was born November 23, 1896. Henry, obviously named for his maternal grandfather, grew up in the shadow and workings of the Schumacher Cotton Mill in Navasota. Though Henry’s father Walter was a bookkeeper at the Schumacher mill in the 1920 U. S. Census record and then a vice-president in the 1930 census data, his son, Henry, took a much different path. Henry followed in the path of his mother Ada, who was a nationally known musician. Henry became a world known musician.

In 1920 Henry was living in New York City where he was organist for three years at the Episcopal Church of the Holy Apostles. The census records show him as a boarder at a house in Manhattan. Only a street or two away was another Manhattan boarder studying music from Pueblo, Colorado – Ida M. Koen. In the 1930 census records, Henry and Ida are married and the parents of two daughters, Emma S., age 8, born in New York and Ida K.,born in South Carolina. At this time the family was living in Nashville, Tennessee where Henry was a music teacher and student at the renowned Ward-Belmont School of Music. He was also the distinguished 1st carillonneur of the school’s 1928 installed carillon of 23 bells. Henry, over time, also composed music for carillons. Both he and Ida had studied from the very best teachers.

The 1940 U. S. Census has Henry and family returned to Navasota. They are residing in the home with Henry’s father, Walter. Henry is recorded as a pipe organ teacher with his wife, Ida, listed as a piano teacher in their private music studio. They taught music to hundreds of Navasota area students. Their daughter Ida dated a Texas A & M corps cadet, Colbert Coldwell of near El Paso. Following Coldwell’s World War II service they were married in March 1945. Meantime Henry’s father Walter, by now head of the Schumacher Cotton Oil Mill, had died in November 1944. Henry’s mother, Ada Schumacher, died the following February. It was then that Henry’s son-in-law Coldwell became the cotton mill manager until 1950, when he resigned and the Coldwell family moved to Clint, Texas to manage his family’s farm. (Coldwell, living in El Paso, died in May 2010 and his wife Ida K. (Wesson), Henry’s daughter, died in June 2013.)

Henry, in 1950, stepped into full management of the Schumacher mill until it ceased operation in 1954. (The Schumacher Cotton Mill stood in Navasota where the Brookshire Grocery store is now located.) Henry died in June 1964 but was preceded in death by his wife, Ida (Koen), nearly ten years earlier in November 1955. All the Wesson burials are in the Oakland Cemetery in Navasota.

With the advent of the development of Wesson Oil from the by-product of cottonseed oil, it can only be a given that some of the cottonseed oil produced by the Schumacher mill became a staple of the popular cooking oil. Is it possible that Henry, at least while he was living in New York in the 1920s, ever met David Wesson, the chemist, who died there in 1934?

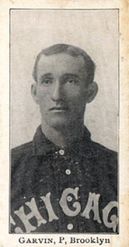

NAVASOTA’S MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL PITCHER

By Betty Dunn

Virgil Lee ‘Ned’ Garvin was born on New Year’s Day, 1/1/1874 on a farm near Anderson in Grimes County. His parents were Adrian and Josephine Garvin. He grew up probably throwing a fast ball to his older brother Eugene, or maybe even his sisters, Lillie and Pearl.

In 1895, at the age of 21, he began his professional baseball pitching career with the Sherman Orphans of the Texas-Southern Minor League. The following year, on July 13th , he began his Major League pitching career for the Philadelphia Phillies.

Better known as Ned Garvin, he pitched for the Phillies for 3 years followed with the Chicago Orphans for a year. In 1901 he was on the Milwaukee Brewers’ roster, followed by the Chicago White Sox in 1902. From 1902 to 1904 he was with the Brooklyn Superbas, finishing 1904 with the New York Highlanders. In 1905 and 1906 he pitched for the minor league teams of the Portland Giants, Portland Beavers, and the Seattle Siwashes.

A baseball chronicler claimed that “Ned Garvin was the tough-luck pitcher of the (1900-1910) decade, if not the hard-luck pitcher of all time…He was pretty much the tough-luck pitcher of the year every year,” as quoted in the New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. He pitched in 181 games with six teams from 1896-1904. Garvin was a heavy drinker who was frequently involved in violent brawls. His 1904 release from the Brooklyn Dodgers followed his beating of the team’s traveling secretary. Despite being among the best pitchers in baseball, he was blacklisted in the National League as a result of his conduct. Subsequently, he was signed by the New York Yankees, the American League, for the remainder of the 1904 season but was not invited back. Garvin's last appearance as a pitcher was in 1906 for the Seattle Rainiers baseball team of the Pacific Coast League. Ned finished his career in 1907 with the Butte Miners as one of the pitching leaders of that Northwestern Minor League with a 20-14 record.

A search of U. S. Census records finds Ned as a 6 year old in 1880 with his parents and siblings near Anderson. In the 1900 census, Ned is recorded in the Navasota household of his parents. That census has Ned listed with a wife, Eugenia, whom he had married in 1898, as well as an infant daughter Gladys.

Ned Garvin died the following year 6/16/1908 of tuberculosis at the young age of 34 at Fresno, California. He is buried there in the Mountain View Cemetery.

By Betty Dunn

Virgil Lee ‘Ned’ Garvin was born on New Year’s Day, 1/1/1874 on a farm near Anderson in Grimes County. His parents were Adrian and Josephine Garvin. He grew up probably throwing a fast ball to his older brother Eugene, or maybe even his sisters, Lillie and Pearl.

In 1895, at the age of 21, he began his professional baseball pitching career with the Sherman Orphans of the Texas-Southern Minor League. The following year, on July 13th , he began his Major League pitching career for the Philadelphia Phillies.

Better known as Ned Garvin, he pitched for the Phillies for 3 years followed with the Chicago Orphans for a year. In 1901 he was on the Milwaukee Brewers’ roster, followed by the Chicago White Sox in 1902. From 1902 to 1904 he was with the Brooklyn Superbas, finishing 1904 with the New York Highlanders. In 1905 and 1906 he pitched for the minor league teams of the Portland Giants, Portland Beavers, and the Seattle Siwashes.

A baseball chronicler claimed that “Ned Garvin was the tough-luck pitcher of the (1900-1910) decade, if not the hard-luck pitcher of all time…He was pretty much the tough-luck pitcher of the year every year,” as quoted in the New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. He pitched in 181 games with six teams from 1896-1904. Garvin was a heavy drinker who was frequently involved in violent brawls. His 1904 release from the Brooklyn Dodgers followed his beating of the team’s traveling secretary. Despite being among the best pitchers in baseball, he was blacklisted in the National League as a result of his conduct. Subsequently, he was signed by the New York Yankees, the American League, for the remainder of the 1904 season but was not invited back. Garvin's last appearance as a pitcher was in 1906 for the Seattle Rainiers baseball team of the Pacific Coast League. Ned finished his career in 1907 with the Butte Miners as one of the pitching leaders of that Northwestern Minor League with a 20-14 record.

A search of U. S. Census records finds Ned as a 6 year old in 1880 with his parents and siblings near Anderson. In the 1900 census, Ned is recorded in the Navasota household of his parents. That census has Ned listed with a wife, Eugenia, whom he had married in 1898, as well as an infant daughter Gladys.

Ned Garvin died the following year 6/16/1908 of tuberculosis at the young age of 34 at Fresno, California. He is buried there in the Mountain View Cemetery.

THOMAS PLINEY PLASTER, BEDIAS EARLY TEXAN

by Betty Dunn

One of the ‘undertold’ early Texas family stories in Grimes County is that of Thomas Pliney Plaster at Bedias. Though Plaster was born in North Carolina he arrived in Texas in 1835 from Giles County, Tennessee settling on a plantation just north outside of Bedias in what was then Montgomery County.

By the following March he served that month as a lieutenant in Captain L. B. Franks’s Ranger company on the northern frontier. On the 2nd day of April that year of 1836 he joined Lt. Col. James C. Neill’s ‘Artillery Corps’ as second sergeant. Within days he was at San Jacinto with General Sam Houston successfully fighting Santa Anna’s marauding army. Significantly, Plaster manned one of the “Twin Sisters” cannon.

Two months later on June 27, 1836 is an ‘untold’ and also ‘unknown’ reason for Plaster’s court martial by Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Rusk. That evening he stood reprimanded before the entire army on parade and dismissed from service. Just eight days later he joined as a private the First Artillery Battalion of Capt. George Washington Poe. By August 1st he had been promoted to quartermaster of the First Cavalry Regiment of the First Brigade of the now Army of the Republic of Texas. He served at Camp Johnson on the Lavaca River until near the end of November of that year of 1836.

Plaster then returned to his family and plantation at Bedias. Over the next twenty years the Plaster plantation grew to just under 3,000 acres. During that time Plaster served Bedias as its postmaster and upon the state’s annexation to the United States in 1846 he was elected to its First Legislature at Austin.

A daughter of the Plasters, Margaret (Plaster) Harrison, told an Indian story to E. L. Blair who related it in his Early History of Grimes County, 1930, on pages 38 and 39.

Margaret’s story: “One night while Mrs. T. P. Plaster was at home alone with her children, her husband having gone to Houston for supplies, an Indian man quietly pushed open the door and entered the room. The mother was too terrified to speak, but the little Margaret, too small to know danger, toddled up to the big Indian and put her arms around his leg in an effort to pull him over to a chair that was being pushed out by her little twin brother. The Indian reached down and took the little girl in his arms as he sat down in the chair. By this time the mother had gotten control of herself and was attempting to show friendliness. She made some coffee and offered the Indian a cup. He took the coffee but refused to drink therefrom until he had first given a spoonful to each of the children and to Mrs. Plaster. He then let it be known that he wanted another cup. When offered more food, however, he refused and, after a time, left as quietly as he had come. Subsequently, this same Indian made several visits to the Plaster home, coming at one time when the father was away from home and sitting the whole night in a corner of a room, leaving a little before daybreak. At another time, he came and warned the family of the approach of a hostile band of Cherokees. Upon another visit, he found Mr. Plaster sick in bed, and when Mrs. Plaster indicated that they were short of food, the Indian left to appear soon thereafter with a wild turkey which he threw at the feet of Mrs. Plaster.”

On January 14, 1858, Plaster’s wife, Dollie, who had made the trek with him from Tennessee in 1835, died giving birth to their 13th child, a daughter Dollie named after her mother. She was only 49 years of age. They were married in Tennessee in 1826. Dollie was buried on the Plaster plantation in what is known as the Plaster-Ross Cemetery.(2) The child also died that day. Cemetery records show that a son, Benjamin, died a few days later on January 21, 1858. He was 19 years of age. He is buried in the Plaster-Ross Cemetery.

Six of Plaster’s children, according to an Ancestry.com family website, were born previous to the Plasters coming to Texas from Tennessee.

Plaster, himself, died of pneumonia three years later in Austin on March 27, 1861 as he served as doorkeeper of the Texas House of Representatives. He was 58 years of age and was buried in the Texas State Cemetery at Austin. His burial site is in Section Two of the Republic Hill Section, Row: S, No. 3.

------------------------------------------------------

by Betty Dunn

One of the ‘undertold’ early Texas family stories in Grimes County is that of Thomas Pliney Plaster at Bedias. Though Plaster was born in North Carolina he arrived in Texas in 1835 from Giles County, Tennessee settling on a plantation just north outside of Bedias in what was then Montgomery County.

By the following March he served that month as a lieutenant in Captain L. B. Franks’s Ranger company on the northern frontier. On the 2nd day of April that year of 1836 he joined Lt. Col. James C. Neill’s ‘Artillery Corps’ as second sergeant. Within days he was at San Jacinto with General Sam Houston successfully fighting Santa Anna’s marauding army. Significantly, Plaster manned one of the “Twin Sisters” cannon.

Two months later on June 27, 1836 is an ‘untold’ and also ‘unknown’ reason for Plaster’s court martial by Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Rusk. That evening he stood reprimanded before the entire army on parade and dismissed from service. Just eight days later he joined as a private the First Artillery Battalion of Capt. George Washington Poe. By August 1st he had been promoted to quartermaster of the First Cavalry Regiment of the First Brigade of the now Army of the Republic of Texas. He served at Camp Johnson on the Lavaca River until near the end of November of that year of 1836.

Plaster then returned to his family and plantation at Bedias. Over the next twenty years the Plaster plantation grew to just under 3,000 acres. During that time Plaster served Bedias as its postmaster and upon the state’s annexation to the United States in 1846 he was elected to its First Legislature at Austin.

A daughter of the Plasters, Margaret (Plaster) Harrison, told an Indian story to E. L. Blair who related it in his Early History of Grimes County, 1930, on pages 38 and 39.

Margaret’s story: “One night while Mrs. T. P. Plaster was at home alone with her children, her husband having gone to Houston for supplies, an Indian man quietly pushed open the door and entered the room. The mother was too terrified to speak, but the little Margaret, too small to know danger, toddled up to the big Indian and put her arms around his leg in an effort to pull him over to a chair that was being pushed out by her little twin brother. The Indian reached down and took the little girl in his arms as he sat down in the chair. By this time the mother had gotten control of herself and was attempting to show friendliness. She made some coffee and offered the Indian a cup. He took the coffee but refused to drink therefrom until he had first given a spoonful to each of the children and to Mrs. Plaster. He then let it be known that he wanted another cup. When offered more food, however, he refused and, after a time, left as quietly as he had come. Subsequently, this same Indian made several visits to the Plaster home, coming at one time when the father was away from home and sitting the whole night in a corner of a room, leaving a little before daybreak. At another time, he came and warned the family of the approach of a hostile band of Cherokees. Upon another visit, he found Mr. Plaster sick in bed, and when Mrs. Plaster indicated that they were short of food, the Indian left to appear soon thereafter with a wild turkey which he threw at the feet of Mrs. Plaster.”

On January 14, 1858, Plaster’s wife, Dollie, who had made the trek with him from Tennessee in 1835, died giving birth to their 13th child, a daughter Dollie named after her mother. She was only 49 years of age. They were married in Tennessee in 1826. Dollie was buried on the Plaster plantation in what is known as the Plaster-Ross Cemetery.(2) The child also died that day. Cemetery records show that a son, Benjamin, died a few days later on January 21, 1858. He was 19 years of age. He is buried in the Plaster-Ross Cemetery.

Six of Plaster’s children, according to an Ancestry.com family website, were born previous to the Plasters coming to Texas from Tennessee.

Plaster, himself, died of pneumonia three years later in Austin on March 27, 1861 as he served as doorkeeper of the Texas House of Representatives. He was 58 years of age and was buried in the Texas State Cemetery at Austin. His burial site is in Section Two of the Republic Hill Section, Row: S, No. 3.

------------------------------------------------------